In our last post of the Wounds by Firearms series, we looked at some guns statistics in the U.S., watched a video on gun safety and saw a dead pig and live watermelon take a few slugs. This week we are going to look at bit closer at why different bullets do different damage and some examples of damage. WARNING: This post has graphic photos.

Bullet Caliber

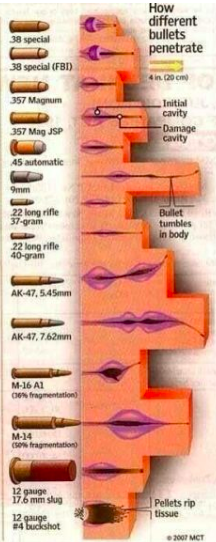

BUT FIRST, let’s look at an illustration of what’s going on inside the body with different caliber bullets. As we saw in last week’s post, a bullet doesn’t simply puncture the body cleanly. The energy causes a gross distortion of the skin and tissue and creates a cavity. If you didn’t watch that video from last week, here ya go.

Caliber Damage

This illustration (1) shows how different bullets penetrate. Sorry it’s a bit fuzzy. The number beside the bullet refers to its caliber. A caliber is the internal diameter, or bore, of gun barrel. A bullet’s caliber corresponds to the gun it is designed to load. Sometimes that diameter, of both gun and ammo, is measured metrically. Sometimes it is measured by the Imperial System using inches. How do you know which measurement is used? The metric will have mm and the Imperial will start with a decimal. Even though a metric caliber and an Imperial caliber are very similar, they are not the exact same diameter. You shouldn’t use metric measured ammo in Imperial measured guns and vice versa. So, a 9mm gun should hold 9mm bullets not .38 bullets even though the caliber of the two are quite similar.

Internal Damage

Don’t assume that guns with the same caliber will do the same amount of internal damage. The bore of a gun doesn’t tell you how long the case of the bullet will be. A bigger, heavier case does not always equate to greater damage. Bullets work best by transferring kinetic energy to the target and that energy rippling out as a shock wave. (We saw that in our last post.) If a bullet passes directly through the body without delivering a shockwave, you won’t create an internal blast effect. But, if that hole created by the bullet is in the right place and causes the target to bleed out, then lack of shock wave isn’t an issue.

Ballistics

For a better understanding of ballistics, read this. It’s, like, a whole science and stuff. And a hole science! Get it? Hole science..bullet hole…never mind. Any who, I am not smart enough to explain it. (I don’t even understand how microwaves work other than magic.) What you need to know is that to kill a character, you don’t have to have a big honking gun! Also, as you can see from the illustration, the design of the bullet can lend itself to tumbling or yawing which equals more damage. If shot in the head with a .22 hand gun, there may not be enough energy created to pass the bullet all the way through the skull. But that little bullet may clang around in there and make a real mess of things.

Here come the pics

Ok, now we come to the part of the show that you’ve all been waiting for: the gross pictures. These are all very tame pictures. I will not show you a head that’s been blown to bits. I’m showing you a few just to give you some ideas. I reached out to two professionals on the subject of bullet wounds. The paramedic said all bullet wounds are different. They are like snowflakes in that respect. Unlike snowflakes, they can be shockingly bloody. That’s what the medical examiner said anyway. She also said that brains go everywhere!

Before the pics, I will provide a space buffer with two videos. The first is one of my favorite people, Hickok45, showing the difference between bullets of the same caliber. The second is some awesome awful martial arts movies.

|

| Soot on hand |

|

| Direct contact range – muzzle imprint |

|

| Direct contact wound – gases released from firing cause charring and stellate pattern. Soot and abrasion ring present. |

|

| Powder tattooing |

|

| Intermediate wound – entry wound irregular as bullet may have tumbled in flight, powder tattooing |

|

| Entry at left, exit at right. Exit wounds can look very different from entry wounds as the bullet distorts in the body. |

(1) Gunshot wounds infographic from Medical College of Wisconsin University, Department of Surgery