Getting anywhere is easier with a map. This is especially true when blocking a fight scene. As a writer, you have to approach the battle the same way a commander would: with the end in mind.

Before going to battle, battle plans are made. Those plans create a strategy that keeps troops movement unified toward a damage goal. Even if that damage goal is ultimately not achieved, it still determines how troops deploy.

Fight Scene Guide – Step-by-Step

Focus of the blocking

The same holds true for a fight on the page. The blocking of a fight scene should be centered around the damage the manuscript requires. Because, just as with real battle strategy, in blocking a fight scene, it is the end that determines the means.

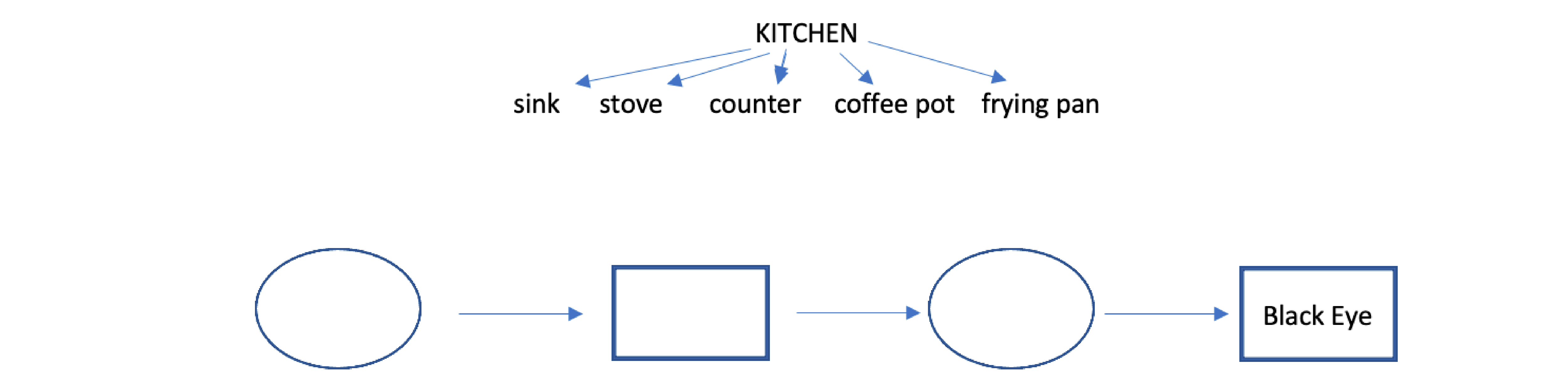

In this post, we are going to map the physical movements of the scene, the route we are taking to injury. With any map, you are shown the area around the route you are taking. You can’t drive north if there is an ocean there. It’s the same with a fight scene. You must know where the fight is taking place to know if the blocking is possible. So, first, decide where the fight is happening. It has a direct impact on the moves. And list everything in that area that may help or impede the action.

Once we have the site of the altercation nailed down, we can start charting movements. Doing all of this, looking at each piece individually, allows us to break the whole into its smaller parts. We are going to reverse engineer this thing.

When your character doesn’t know how to fight

The first item we will map is our destination, our damage goal. From there we will move backward. On the note of damage, be sure that it suits the scene and serves the story. If a character needs a black eye, don’t go at them with a mace. While the mace may suit your epic fantasy, it doesn’t serve the story because a mace will knock a mud hole in a skull and that isn’t what we are going for.

The injury goal

When you’re blocking your fight scene, aim to achieve your injury goal as easily as possible. That not only allows the reader to more easily follow the action but, also, the more complicated the route, the less focus there is on the destination. It’s that injury we want to focus on for several reasons:

It keeps attention on the character with the injury

It gives us the opportunity to add in sensory details such as pain

It connects the reader to the scene because every reader, regardless of fight knowledge, understands pain

Mapping it out

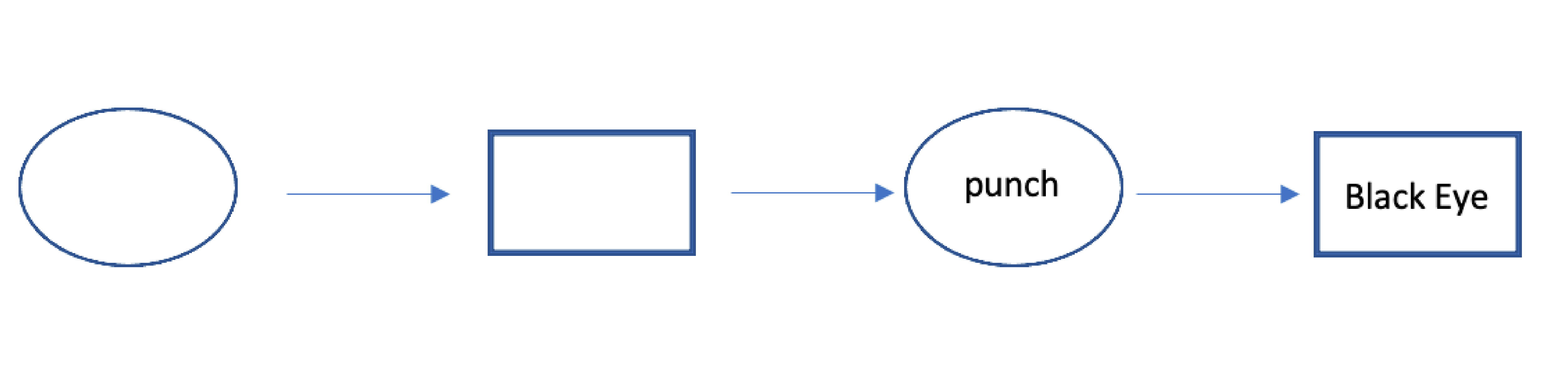

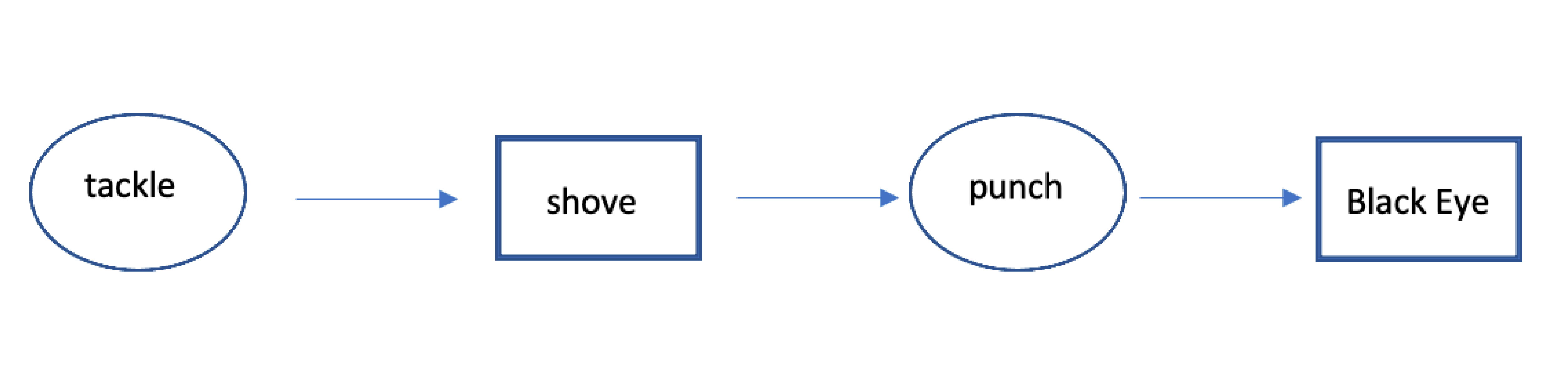

I will do another post on determining the best injury for the scene. For now, let’s make that injury goal a black eye. We will put the injury goal at the end and walk backward noting three movements. Yes, we are blocking the fight scene backwards. The squares refer to “B,” the injured character. The circles are “A,” the character who injures. Above the map, note the site of the fight and anything that might be in that area.

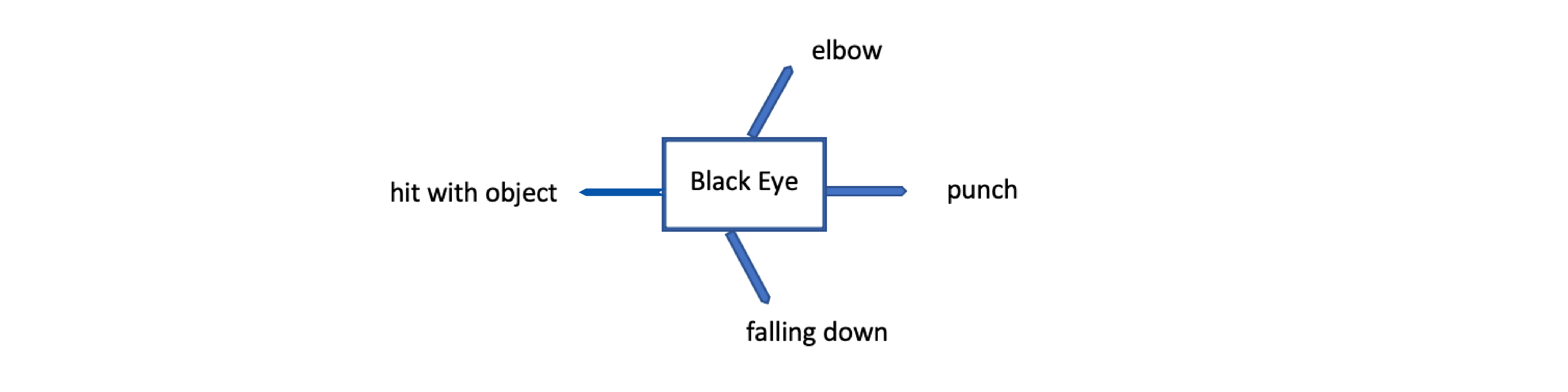

From the damage goal, draw little branches with movements that could achieve it.

From these movements, branch more ideas including the problems associated with them that might preclude them from being an option for the scene. For example, falling and hitting the face might also break the cheek bone or nose. The same can hold true with the other options, but those are also items that fit more directly into that orbital bone area. A floor, however, is flat and will hit the entire side of the face.

One of my mantras is “how can I make this easier?” So, let’s pick an easy option that people are familiar with. We will achieve the black eye with a punch. Don’t worry about what kind.

Now we fill in the other spots with fight moves. For now, don’t worry if they make sense.

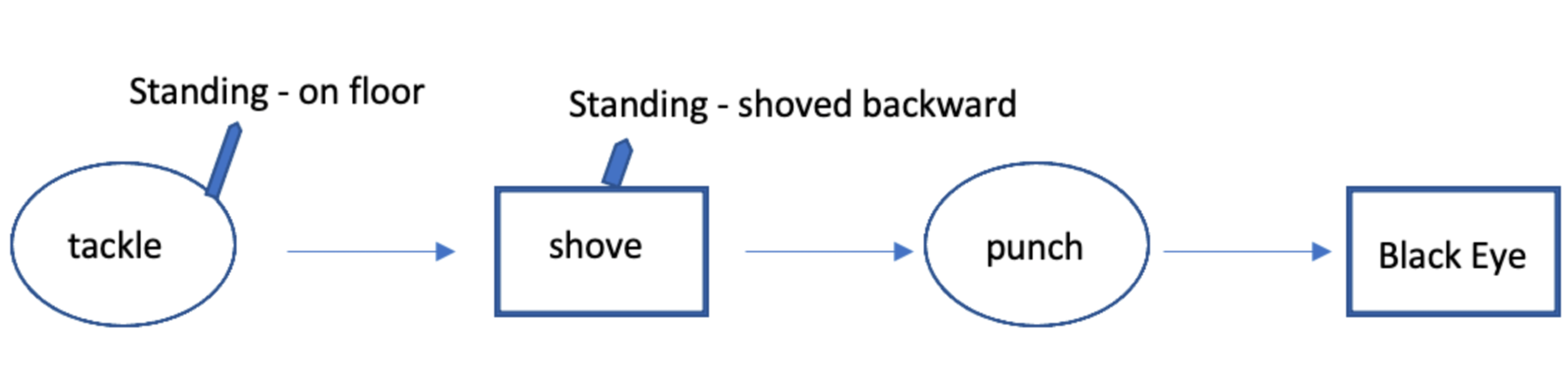

Once we have the movements down, write the positioning of the body before and after each.

Once we have the movements down, write the positioning of the body before and after each.

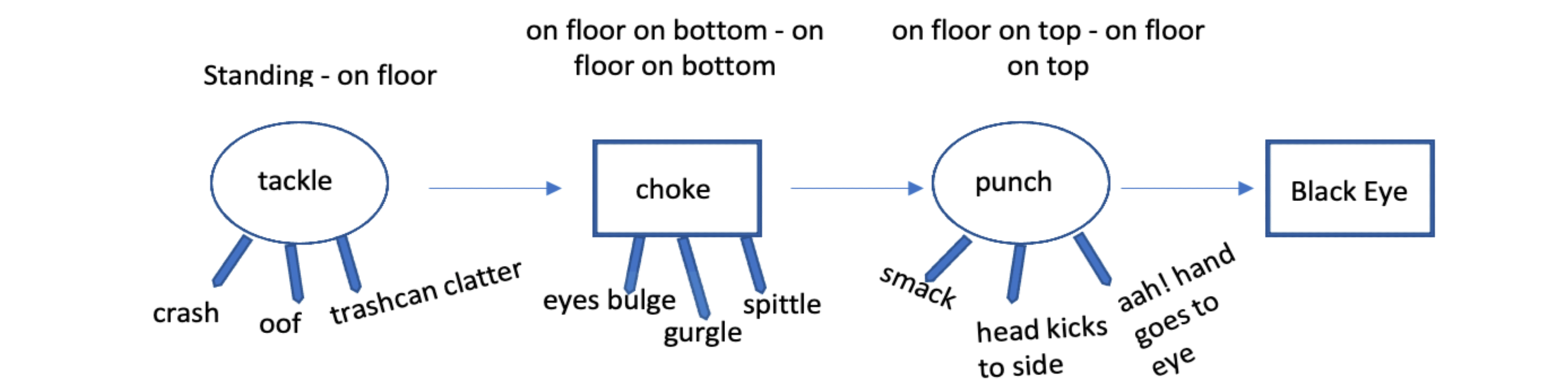

And here we see our first problem. If person A tackles person B and they are both on the floor, the shove won’t be possible. We have to change one of those. I will change the movement of B to a choke because that can happen on the floor from many positions. But, because B is tackled, he is likely on his back as that’s the trajectory of the movement.

Once the movements agree, make a list of sensory details. If you were standing in the scene of the fight, what might you see, hear, smell, and feel physically? Don’t include emotion words as adrenaline dulls emotions.

Also, remember the location of the fight. What might get in the way? What might be knocked over or broken? If it is first person, what might the character taste? Pick items off the list and write them down on the map where they make sense. For example, it makes sense that when character B is tackled, the two characters run into cabinetry or trashcans.

Sample scene

Ok, here we go. Now you have a ton of info that you can use. Or not! You don’t have to use all or anything that you’ve mapped. It may be that the map got your brain going in another direction and that is great! The map did its job. Regardless, you now have something visual, in front of you, to work with. Look the map over and see what else you can add, maybe some dialogue or details that only now are popping into your head. Then, let’s see what we can put together. A is Al. B is Bob.

Al drove his shoulder into Bob’s stomach and the two went to the floor. Bob’s head hit the kitchen tile with a low-pitched smack.

Time turned viscous behind a field of stars as Bob’s eyes scanned the kitchen, narrowing his eyes to focus. He looked up at Al. Veins rolled fat and thick on Al’s temples as he looked down. The sound from his quickly moving mouth was muffled behind the static in Bob’s brain.

A slap pitched Bob’s head to the side. The cold tile against his cheek and ear pulled him away from the swirling vacuum in his skull. He gripped Al’s throat with both hands. Al’s eyes opened wide. He flailed against the grip, gurgling, spitting and hissing.

Bob’s arms and hands were heavy and numb. He narrowed his eyes, focusing them on his thumbs pressing down on the bony give of Al’s Adam’s apple.

From the corner of his eye, Bob saw Al’s fist.

The world splashed black.

Well, there you have it. Now, go through that short scene. Circle what you like, cross out what you don’t. How would you reconstruct it? What opportunities were missed? What images stick with you. Make that scene YOUR scene. Re-map it, re-work it until you are sitting on the cold kitchen floor watching it first-hand.

I hope this helps. Give mapping a try. The process of reverse engineering is great for folks who need a visual or struggle to get the scene out of their head. Remember, there’s no one way to write a fight scene. And, there’s no one way to lay the ground work for it.

Until the next round at FightWrite™, get blood on your pages!

Magnificent website. Plenty of useful information here. I’m sending it to some friends ans also sharing in delicious. And naturally, thanks for your sweat!

It is the best time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I’ve read this post and if I could I desire to suggest you some interesting things or advice. Maybe you could write next articles referring to this article. I want to read more things about it!

Very interesting info!Perfect just what I was looking for!

Nice post. I be taught one thing tougher on different blogs everyday. It’ll at all times be stimulating to read content material from other writers and apply a little something from their store. I’d choose to make use of some with the content material on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll offer you a link in your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

Great write-up, I¦m normal visitor of one¦s site, maintain up the excellent operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

Really nice design and fantastic content material, hardly anything else we require : D.

I genuinely enjoy reading on this internet site, it holds great articles.

I’m really impressed with your writing skills as smartly as with the structure for your blog. Is that this a paid subject or did you modify it your self? Either way keep up the excellent high quality writing, it’s uncommon to look a great blog like this one today..

I am no longer sure where you’re getting your information, but good topic. I must spend some time learning much more or understanding more. Thanks for wonderful info I used to be looking for this information for my mission.

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

You are my inhalation, I own few blogs and very sporadically run out from to brand.

Well I definitely liked reading it. This information provided by you is very constructive for proper planning.

Perfectly written subject matter, regards for entropy.

You have brought up a very excellent points, appreciate it for the post.

Hi would you mind letting me know which webhost you’re using? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different web browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you suggest a good hosting provider at a fair price? Thanks, I appreciate it!

I don’t usually comment but I gotta admit regards for the post on this perfect one : D.

I believe this is one of the most vital information for me. And i’m happy reading your article. But should statement on some common issues, The website taste is wonderful, the articles is really nice : D. Excellent process, cheers

I like the valuable info you provide in your articles. I will bookmark your blog and check again here frequently. I am quite sure I will learn lots of new stuff right here! Good luck for the next!

Awsome blog! I am loving it!! Will be back later to read some more. I am taking your feeds also.

superb post.Never knew this, thanks for letting me know.

F*ckin¦ remarkable issues here. I¦m very satisfied to see your post. Thank you a lot and i am having a look ahead to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a mail?

I am constantly searching online for tips that can help me. Thx!

You actually make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this matter to be actually something which I think I would never understand. It seems too complex and extremely broad for me. I’m looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

You completed a number of fine points there. I did a search on the subject matter and found nearly all people will go along with with your blog.

You really make it appear so easy together with your presentation however I in finding this matter to be actually one thing that I think I would by no means understand. It kind of feels too complicated and extremely large for me. I am taking a look ahead to your subsequent submit, I’ll try to get the hold of it!